There is something very delicate about supporting a loved one in times of difficulty, illness, struggle. For some the nuances of navigating and holding space is a natural instinct … and for some it takes a little extra effort and awareness. This coining of “comfort in, dump out” or “the ring theory” is not my own … I came across it and it resonated so true that I wanted to share it as I feel it describes a way of being that is critical to being there for someone who is going through a challenging time.

I feel it outlines and expresses the idea simply and in a way that we can all hopefully understand and appreciate so that we can all better support our loved ones … so we can balance our own experiences and emotions while acknowledging the greater burden carried by those directly affected and immediately involved.

And it not only applies to illness but “all kinds of crises - medical, legal, even existential. It's the 'Ring Theory' of kvetching. The first rule is comfort in, dump out.”

"When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the center of the crisis, the goal is to help. Listening is often more helpful than talking. But if you're going to open your mouth, ask yourself if what you are about to say is likely to provide comfort and support. If it isn't, don't say it. Don't, for example, give advice. People who are suffering from trauma don't need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, 'I'm sorry' or 'This must really be hard for you' or 'Can I bring you a pot roast?' Don't say, 'You should hear what happened to me' or 'Here's what I would do if I were you.' And don't say, 'This is really bringing me down.'"

I believe our intention as humans is not to be selfish, insensitive or inappropriate however in times difficulty, having to sit with discomfort, or fear we may default and forget which direction is best to express our feelings. Hopefully this can shed a little light.

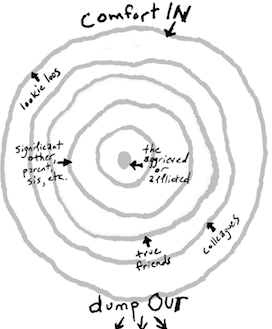

Draw a small circle and put the name of the person closest to the tragedy in the middle of that circle. Then, draw a larger (concentric) circle and put the name of the person closest to the centre person – for adults, this is usually a spouse or partner, but may be children, parents, a colleague, or closest friend. Keep drawing larger circles around the other circles and add the layers of people–close friends, more distant friends, members of the community, etc. Here are the rules:

The person in the centre circle can cope any way he/she wants. The job of those in the larger circles is to listen and support.

When talking to a person in a circle smaller than yours, remember that you are talking to someone closer to the tragedy. Your job is to help. You are not allowed to dump your anger, fear, or grief to people in circles smaller than yours.

Express these emotions to those in your circle or larger circles.

The concept is simple–“comfort in, dump out.”

And remember, everyone copes in his or her own way. Some people cope best by sharing, others prefer to grieve privately. Both are valid coping mechanisms – private does not mean denial! It’s perfectly healthy to look for comfort in the normalcy of day-to-day life. So don’t be surprised if someone going through a crisis or tragedy chooses to brush the topic aside – and please don’t press!

If you want to help, listen and/or offer practical help (specific offers of help with kids, errands, food – not advice on how to handle the situation, though!). Don’t insert your own grief, anger, or preferred coping mechanisms into someone else’s crisis. Seek support for yourself from those in your same situation (same circle), or those further from the tragedy (larger circles).

Article from LA times by Susan Silk and Barry Goldman

When Susan had breast cancer, we heard a lot of lame remarks, but our favourite came from one of Susan's colleagues. She wanted, she needed, to visit Susan after the surgery, but Susan didn't feel like having visitors, and she said so. Her colleague's response? "This isn't just about you."

"It's not?" Susan wondered. "My breast cancer is not about me? It's about you?"

The same theme came up again when our friend Katie had a brain aneurysm. She was in intensive care for a long time and finally got out and into a step-down unit. She was no longer covered with tubes and lines and monitors, but she was still in rough shape. A friend came and saw her and then stepped into the hall with Katie's husband, Pat. "I wasn't prepared for this," she told him. "I don't know if I can handle it."

This woman loves Katie, and she said what she did because the sight of Katie in this condition moved her so deeply. But it was the wrong thing to say. And it was wrong in the same way Susan's colleague's remark was wrong.

Susan has since developed a simple technique to help people avoid this mistake. It works for all kinds of crises: medical, legal, financial, romantic, even existential. She calls it the Ring Theory.

Draw a circle. This is the centre ring. In it, put the name of the person at the centre of the current trauma. For Katie's aneurysm, that's Katie. Now draw a larger circle around the first one. In that ring put the name of the person next closest to the trauma. In the case of Katie's aneurysm, that was Katie's husband, Pat. Repeat the process as many times as you need to. In each larger ring put the next closest people. Parents and children before more distant relatives. Intimate friends in smaller rings, less intimate friends in larger ones. When you are done you have a Kvetching Order. One of Susan's patients found it useful to tape it to her refrigerator.

Here are the rules. The person in the centre ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can kvetch and complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, "Life is unfair" and "Why me?" That's the one payoff for being in the centre ring.

Everyone else can say those things too, but only to people in larger rings.

When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the centre of the crisis, the goal is to help. Listening is often more helpful than talking. But if you're going to open your mouth, ask yourself if what you are about to say is likely to provide comfort and support. If it isn't, don't say it. Don't, for example, give advice. People who are suffering from trauma don't need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, "I'm sorry" or "This must really be hard for you" or "Can I bring you a pot roast?" Don't say, "You should hear what happened to me" or "Here's what I would do if I were you." And don't say, "This is really bringing me down."

If you want to scream or cry or complain, if you want to tell someone how shocked you are or how icky you feel, or whine about how it reminds you of all the terrible things that have happened to you lately, that's fine. It's a perfectly normal response. Just do it to someone in a bigger ring.

Comfort IN, dump OUT.

There was nothing wrong with Katie's friend saying she was not prepared for how horrible Katie looked, or even that she didn't think she could handle it. The mistake was that she said those things to Pat. She dumped IN.

Complaining to someone in a smaller ring than yours doesn't do either of you any good. On the other hand, being supportive to her principal caregiver may be the best thing you can do for the patient.

Most of us know this. Almost nobody would complain to the patient about how rotten she looks. Almost no one would say that looking at her makes them think of the fragility of life and their own closeness to death. In other words, we know enough not to dump into the centre ring. Ring Theory merely expands that intuition and makes it more concrete: Don't just avoid dumping into the centre ring, avoid dumping into any ring smaller than your own.

Remember, you can say whatever you want if you just wait until you're talking to someone in a larger ring than yours.

And don't worry. You'll get your turn in the centre ring. You can count on that.

Sending courage, hope, love and light to all experiencing the storm.

- Krista McKeachie